Flowers & Medicine

Flowers have played a significant role in society, focusing on their aesthetic value rather than their food potential. This study’s goal was to look into flowering plants for everything from health benefits to other possible applications. This review presents detailed information on 119 species of flowers with agri-food and health relevance. Data were collected on their family, species, common name, commonly used plant part, bioremediation applications, main chemical compounds, medicinal and gastronomic uses, and concentration of bioactive compounds such as carotenoids and phenolic compounds.

In this respect, 87% of the floral species studied contain some toxic compounds, sometimes making them inedible, but specific molecules from these species have been used in medicine. Seventy-six percent can be consumed in low doses by infusion. In addition, 97% of the species studied are reported to have medicinal uses (32% immune system), and 63% could be used in the bioremediation of contaminated environments. Significantly, more than 50% of the species were only analysed for total concentrations of carotenoids and phenolic compounds, indicating a significant gap in identifying specific molecules of these bioactive compounds. These potential sources of bioactive compounds could transform the health and nutraceutical industries, offering innovative approaches to combat oxidative stress and promote optimal well-being.”

Learn more here: Exploring Plants with Flowers: From Therapeutic Nutritional Benefits to Innovative Sustainable Uses via NIH.

Nerd

Spent two days nerding out at AAMC’s “2026 Emerging Technologies for Teaching and Learning: Digital Demonstrations Virtual Conference” and loved it.

What landed for me:

- AI is an incredible tool when it comes to synthesizing data and finding patterns in these massive sets, but at this point in its development, it fails to convey the passion and excitement that come with teaching a subject you love and live through your being. It’s that energy, transmitted when we are talking about a topic, that engages and captures learners’ attention. It’s our story, and the narrative we create, that helps the learner retain the moral on a cellular level. Some people think we can offload that to AI, but the reality is that there’s nothing more satisfying (to me) than looking into the eyes of another human being and saying, “Oh my gosh, you are never going to believe this! NASA just got this crazy, super-close image of Jupiter, and it looks just like van Gogh’s Starry Night…and!!”

- AI can strengthen clinical reasoning teaching if we design it like a coach and not an answer machine. When I think about faculty development for healthcare professionals, AI can help craft a learning journey tailored to their needs and interests. However, it’s still important to connect a human in that process because they represent not just the coach, but also the learner.

- Narrative assessment and feedback can be improved at scale, but only if we protect meaning, context, and fairness. We have a responsibility to educate faculty on how to write meaningful assessments about their learners. AI can assist by providing a framework for that, but at the end of the day, the quality of the data going in is more important.

I am leaving with a shortlist of ideas to bring into faculty development and program improvement work, especially around assessment quality, defensible decision-making, and accreditation readiness. For accreditation, I think many medical education programs are exploring the use of AI. Based on what I learned, accreditation bodies have not provided much guidance on the use of AI in reporting. One institution wisely suggested that you disclose the use of AI in the reporting process and that humans reviewed both the input and output data. Great advice and great conference!

#MedicalEducation #AI #Assessment #FacultyDevelopment #ProgramEvaluation #EthicsInAI

AI & Medical Education Conferences 2026

Here are some major upcoming events in 2026 where artificial intelligence intersects with medical education, health sciences, and university-level research. These include conferences, summits, and academic gatherings that are either explicitly focused on AI in medical teaching and training, or closely related fields (AI in healthcare, precision medicine, digital innovation) with strong relevance to universities and educators:

🎓 Medical Education and AI-Focused Conferences

1. Innovations in Medical Education Conference (University of Miami) – March 26-27, 2026

A dedicated two-day conference on integrating AI into medical education, with panels and workshops on curriculum design, teaching technologies, ethics, and AI tools for assessment and learning. 2. International Conference on Medical Education, Health Sciences & Patient Care – Paris, October 21-22, 2026

Broad medical education conference with sessions spanning innovation, pedagogy, and technological applications including AI in training and healthcare delivery. 3. 23rd Innovations in Medical Education (USC Online Conference) – February 11-12, 2026

Annual medical education event hosted by the University of Southern California, offering virtual participation and global engagement in education innovation (likely includes AI-related topics). 4. 8th Midlands Medical Education Conference – 2026 (UK)

Regional medical education event including themes on embracing AI and digital tools in medical teaching across universities.

🧠 AI and Medicine / Healthcare Innovation Events

These gatherings are broader than pure medical education but are highly relevant to academics, researchers, and faculty exploring AI in healthcare teaching, research skills, and clinical workflows:

5. AIME 2026 – Artificial Intelligence in Medicine – Ottawa, Canada, July 7-10, 2026

International conference on AI and medicine hosted at the University of Ottawa with deep ties to academic research and cross-disciplinary scholarship. 6. International Conference on Precision Medicine and AI Healthcare – Prague, July 27-28, 2026

Global forum for clinicians, researchers, and educators on AI’s role in precision medicine and data science, often including academic perspectives. 7. AI4Health: Improve Health Through Artificial Intelligence Conference – University of Florida campus (2026)

University-hosted event combining AI healthcare research, training opportunities, and academic discussion. 8. AI Summit (Mayo Clinic) – Rochester, MN, June 4-5, 2026

While broader in scope, this summit addresses AI in clinical settings and systems which complements medical education on real-world applications.

🎓 Education & AI Broadly Relevant

9. AI + Education Summit 2026 (Stanford Accelerator for Learning & HAI)

Though not solely medical, this high-impact summit brings AI education thought leaders, including applications relevant to health professions education and curriculum design.

📌 Tips for Academic Participation

- Early planning and abstract submissions often open months ahead of events like AIME and HealthAI2026.

Many conferences offer workshops or tracks on AI ethics, curriculum innovation, and experiential learning that are especially useful for faculty and graduate scholars.

Check university event calendars (e.g., Stanford HAI, medical school education departments) for unofficial symposia or local AI in medical education workshops throughout the year.

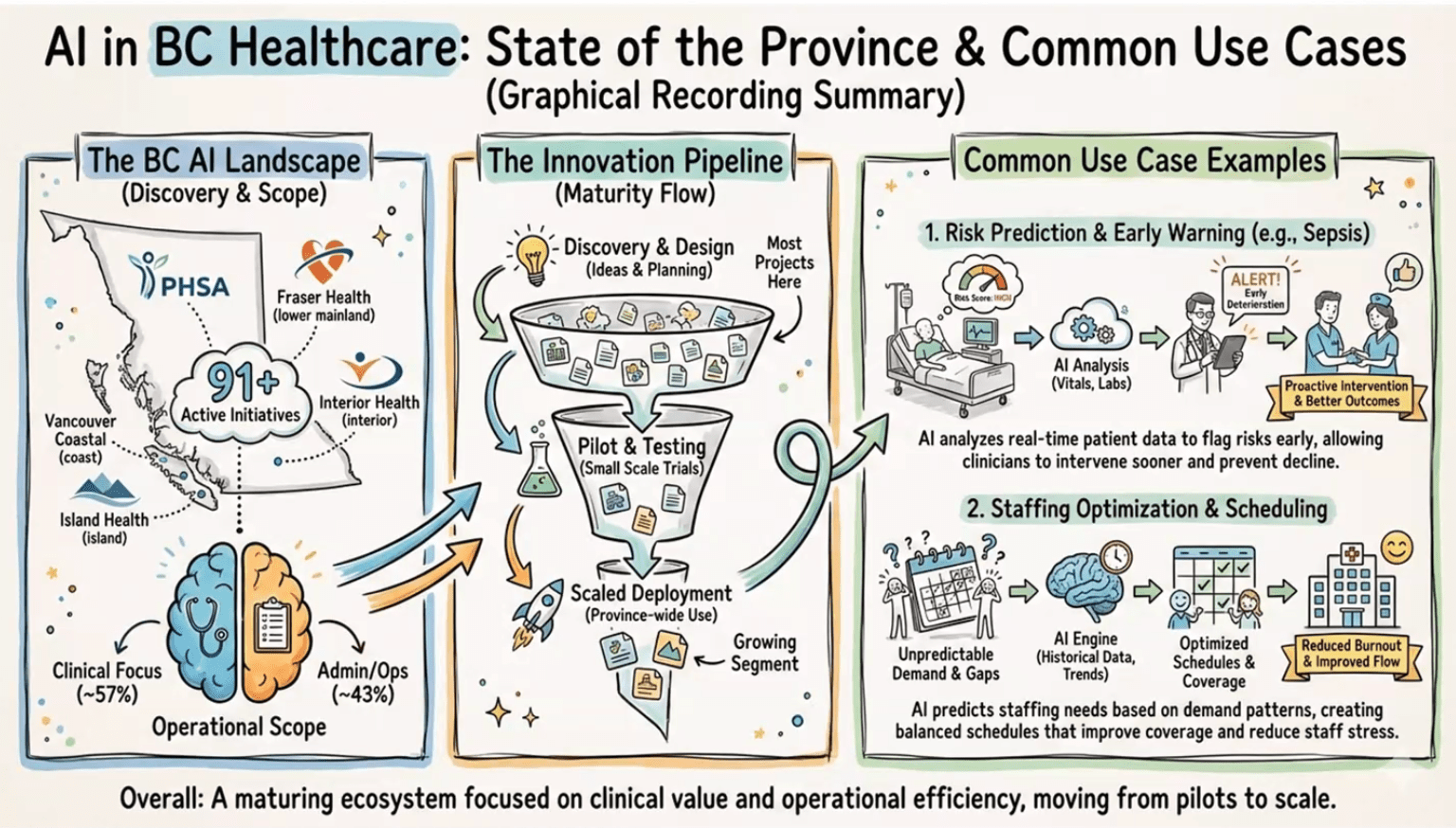

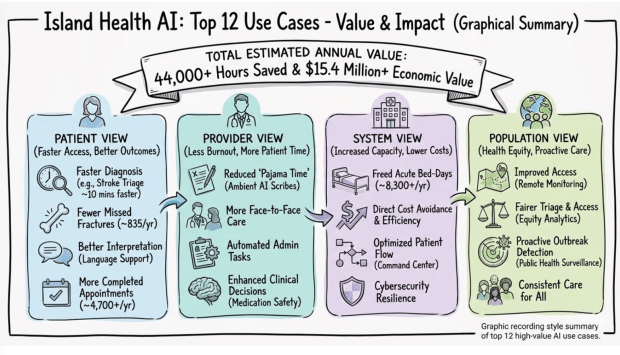

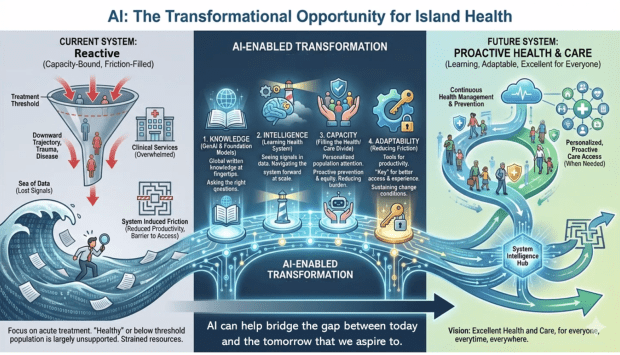

Hype to Hospital

This evening I attended the “From Hype to Hospital: How AI is being used in Healthcare and Research” hosted in British Columbia, Canada.

We’re surrounded by data in our healthcare system, but our ability to convert it into timely, trustworthy decisions is still limited by workflow, infrastructure, and governance. Provincial data collection continues to be labour intensive, often manual, and delayed.

As it was reported this evening, in trauma care, there can be a 12-18 month lag between what happens in the Emergency Department and Trauma Service, and what ultimately lands in registries, dashboards, and system-level reports. Check out the article “iROBOT: Implementing Real-time Operational dashBOards for Trauma care” to learn more: https://lnkd.in/gvBQKMgs

Other interesting points from presenters include:

+ Structured data is easy to analyze, narrative data holds the nuance that can change risk and interpretation.

+ AI can speed screening and reporting, reduce false positives, and support real-time dashboards, if evaluated honestly.

+ In BC, common use cases are emerging: early warning (sepsis, deterioration), staffing and scheduling, operational intelligence.

+ The hard part is the pipeline: discovery to pilot to scaled deployment, many projects stall before impact.

+ Implementation risks are real: trust (confabulation, over-reliance), privacy, environmental cost, workforce disruption.

My takeaway: We have a responsibility to educate and train healthcare practitioners in the use of AI, and to start asking critical questions about how it will affect patient care.

Slides attached are from Graham Payette’s AI BC briefing.

Primary Compassionate Care Hub

Today I get to say something I have dreamed of saying for years: we did it!

The Primary Compassionate Care Initiative now has a place to call home. Our Primary Compassionate Care Hub is real, it is built, and it is open. It is bright, welcoming, and intentionally designed for what matters most, people, learning, and community.

This Hub has been a long time coming. It grew out of Dr. Aisha Liman’s simple belief that keeps guiding everything we do at the Primary Compassionate Care Initiative: care is not only a clinical act, it is a culture we build together. We wanted a home for that culture, a place where learners, mentors, clinicians, and community members can gather, teach, and grow side by side.

A space designed for learning that feels human

When you walk in, you can feel the purpose immediately. The Hub includes a training and teaching room set up for workshops, small group sessions, and hands-on learning. There are flexible chairs and work tables, a presentation area, and a layout that supports real interaction, not passive sitting.

We also created comfortable tiered seating with bright cushions, a simple detail that quietly changes the energy of a room. It invites discussion. It invites listening. It invites people to stay.

In other words, this is not a room designed only to deliver content. It is a room designed to build confidence, conversation, and competence.

A “community begins with us” moment, made physical

One of my favorite elements is the message at the entrance: “Community begins with us.” It captures what we are trying to do, not just teach skills, but create a place where belonging and responsibility are visible, shared, and practiced.

This Hub is meant to be a meeting point for learners and the communities they serve. It is a space where we can run mentorship sessions, leadership development, health education programming, team-building activities, and practical skill-building workshops grounded in compassion.

Yes, we even built the warmth into the walls

There is another sign in the space that made me smile because it is exactly right: “Compassion is Brewing.” It sits above a warm, welcoming café-style area that feels like a natural gathering place. Because sometimes the most meaningful learning happens before the session starts, during the conversations, the laughter, the quiet questions, and the “Can I ask you something?” moments.

We wanted the Hub to feel energizing and calm at the same time. The lighting, the wood tones, the bright colors, and the clean design all contribute to that balance. It feels professional, but not sterile. It feels modern, but still personal.

What this Hub will be used for

This Hub is a working space, and we have big plans for it, including:

- mentorship and academic support for health practitioner learners

- workshops on communication, teamwork, and patient-centered care

- community health education sessions

- faculty and preceptor development

- collaborative project meetings and design sessions

- leadership and professional identity development

Most importantly, it will be a place where learners can practice building trust, showing up with humility, and delivering care that is both competent and kind.

Gratitude, and what comes next

I am deeply grateful to everyone who helped make this possible. A space like this is never built by one person. It is built by shared values, steady work, and people who refuse to let good ideas stay only in the imagination.

This Hub is a milestone, and it is also a beginning.

Because now we get to do what we came here to do: grow a new generation of compassionate, community-grounded health professionals, and support them with the structure, mentorship, and environment they deserve.

Thank you for believing in this dream with us.

More soon, and if you are nearby and want to visit, collaborate, or support a workshop, I would love to hear from you.

With gratitude,

Jacqueline

Course: Trauma & Disaster Team Response

When Disaster Hits, Family Medicine Is Still the Front Door

Disasters and major trauma can feel like “someone else’s job” until the day your clinic, urgent care, or community hospital becomes the first place people arrive. In those moments, what matters most is not just clinical knowledge, it is teamwork, role clarity, and a shared plan.

A useful option is Trauma and Disaster Team Response, a free online course on SURGhub, offered through the McGill University Health Centre, Centre for Global Surgery. It is built around multidisciplinary trauma and disaster response, with lectures and quizzes, and it is designed to strengthen how teams function under pressure.

Why it matters for family medicine

Family physicians are often central to stabilization, triage, transfer decisions, and supporting staff and communities in the aftermath. This training can help build a common language for response, especially in rural and community settings where resources and staffing can shift quickly.

What you can take back to your team

- Clearer roles during urgent resuscitation and surge situations

- More confidence with transfer readiness and escalation

- A framework for thinking about disaster response as a system, not just a single patient

- A nudge to turn preparedness into practical clinic improvements (call trees, checklists, short drills)

Learn more here at McGill University’s SURGhub. And a big thank you to Ali for sharing this resource with me. His work in this area is incredibly admirable and much needed.

Acquaintances

Under the cherry blossoms

strangers are not

really strangers

Silence

Spring is leaving

Birds cry, and in the fishes’ eyes

are tears.

~ Chiyo-ni

Bloom!

“How much do we really know about the plants and flowers in our gardens and vases? Beyond their beauty, many have surprising stories of exploration, exchange, and discovery. In Bloom takes visitors from Oxford across the world and back, tracing the journeys that some of Britain’s most familiar blooms travelled to get here. Featuring more than 100 artworks, including beautiful botanical paintings and drawings, historical curiosities and new work by contemporary artists, the exhibition follows the passion and ingenuity of early plant explorers and the networks that influenced science, global trade and consumption. Visitors will learn how plants changed our world and left a legacy that still shapes our environments and back gardens today.” ~ Ashmolean Museum, Bloom Exhibit 2026

Art by Claire Desjardins